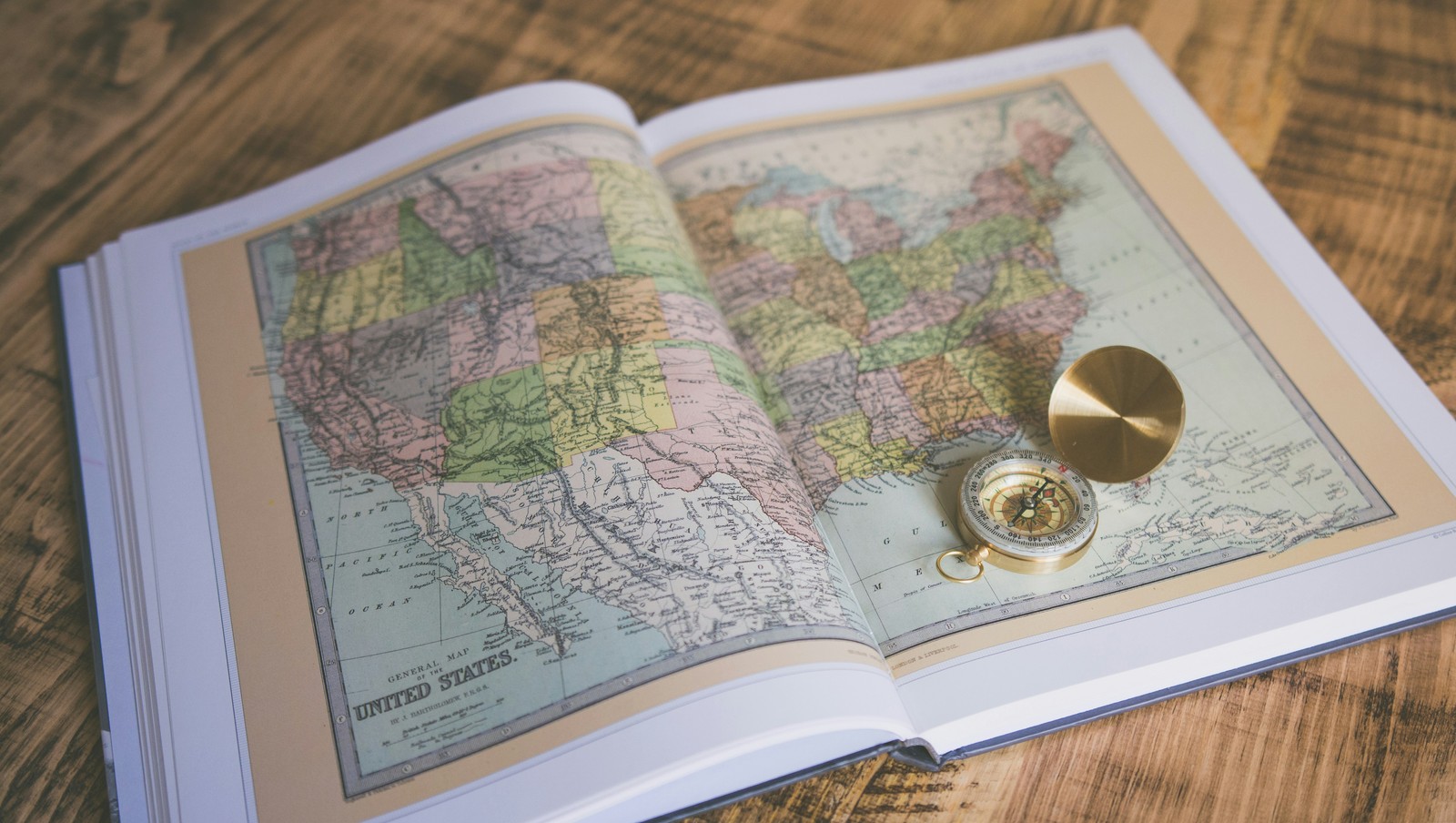

Lands that were only dreams

Superior, Transylvania, Sequoyah, and other states that never were

Image: Chris Lawton

The map of the United States could have looked very different—perhaps with around 70 states, each having its own capital and constitution. For example, have you ever heard of the proposed states of Franklin or Westsylvania? And can you guess where Superior was supposed to be located? Let’s dive into 13 states that almost—but never—found a place on the map.

1

Superior

Image: Brian Beckwith

As we know, Michigan is divided into the Upper and Lower Peninsulas. The discussion about whether the Upper Peninsula should become its own state dates back as far as 1858.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, residents of the region proposed creating the State of Superior , named after the Great Lake that defines the region. Although the movement never gained enough traction, some people still support the idea today, even though Superior would become the state with the smallest population.

2

Jefferson

Image: Kirk Thornton

Jefferson was a proposed state, much like Washington was before it became a state. Picture this: a state straddling Northern California and Southern Oregon, rich in timber and minerals. This was the vision for Jefferson , first proposed in the mid-19th century and revived in 1941.

Residents even declared a symbolic "secession" and distributed pamphlets proclaiming their independence. However, World War II shifted priorities , and the movement eventually fizzled out.

3

Deseret

Image: Wolfgang Hasselmann

Mormon settlers had big dreams in 1849—they proposed Deseret , a massive theocratic state . The name, meaning "honeybee" in the Book of Mormon , symbolized industry and cooperation. But Congress wasn’t exactly buzzing with enthusiasm.

Instead, Congress created the smaller Utah Territory , which at the time included present-day Utah as well as parts of Nevada, Colorado, and Wyoming.

4

Sequoyah

Image: Nina Luong

In 1905, Native American tribes in eastern Oklahoma proposed the State of Sequoyah , named after the Cherokee scholar who created the Cherokee syllabary .

It was a bold move to create a Native-majority state. However, Congress chose instead to merge the area with Oklahoma Territory to form the state of Oklahoma . The constitution drafted for the proposed State of Sequoyah went on to influence the final Constitution of Oklahoma.

5

Lincoln

Image: Clark Van Der Beken

The proposed State of Lincoln had multiple identities. One version placed it in eastern Washington and northern Idaho. Although the name was intended to honor Abraham Lincoln, other names, such as Columbia and Eastern (East) Washington , were also considered.

Another proposal envisioned Lincoln in southern Texas. This version reportedly had a prepared constitution and a distinctive red flag featuring Lincoln’s face inside a yellow circle.

6

East and West Jersey

Image: Nick Fewings

Can you imagine two New Jerseys? Back in 1674, when the area was still a British province, New Jersey was divided into East Jersey and West Jersey , each with its own government and constitution.

But the separation lasted only 28 years . The territories were rejoined in 1702, and the first New Jersey state constitution wasn’t adopted until 1776, following independence from Britain.

7

Franklin

Image: Dan Mall

The State of Franklin was another plan, except this one worked, for a while. In 1784, settlers in eastern Tennessee had had enough with what they saw as North Carolina’s neglect. They declared independence and formed the State of Franklin , named after Benjamin Franklin, of course.

For four years, Franklin operated as a de facto state , complete with its own constitution and government. However, Congress refused to recognize it, and by 1788, the State of Franklin ceased to exist.

8

Transylvania

Image: Julia Volk

Transylvania (from the Latin for "beyond the woods" ) is more than just a remote land of vampire legends—it was also nearly the name of a short-lived American colony in what is now mostly Tennessee and parts of Kentucky.

In 1775, land speculator Richard Henderson struck a deal with the Cherokee to create the Colony of Transylvania , in parts of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia. But Virginia and North Carolina declared the venture illegal. Still, the name lives on today in Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky.

9

Nickajack

Image: lauren barton

During the Civil War, Union sympathizers in northern Alabama, northern Georgia, and eastern Tennessee proposed the creation of the State of Nickajack . The name came from a Cherokee village, but the idea never gained much traction.

Today, the Nickajack Dam and Nickajack Lake reservoir mark areas that would have fallen within the boundaries of this proposed state.

10

Absaroka

Image: Mohan Nannapaneni

Have you ever heard of Absaroka ? During the Great Depression, residents of parts of Wyoming, South Dakota, and Montana proposed the creation of the State of Absaroka , named after the Crow Nation’s word for "children of the large-beaked bird."

The movement was largely a symbolic protest against federal neglect. Absaroka even had its own license plates and a self-declared "governor," but the state never came to fruition.

11

Westsylvania

Image: Isaac Wendland

Yet another -vania . In the late 18th century, settlers west of the Appalachian Mountains proposed the creation of the State of Westsylvania . Frustrated by neglect from eastern state governments—especially Virginia and Pennsylvania—they wanted a state of their own.

But like many other separatist efforts, the proposal was rejected by Congress and never became a reality.

12

Madison

Image: Library of Congress

Another president nearly had a state named after him—but didn’t. The name of the fourth U.S. president, James Madison, was once proposed for the area that is now part of the Dakotas.

In the late 19th century, residents of what is now southwestern North Dakota proposed the creation of the State of Madison . However, the idea faced a major hurdle: Congress was already considering dividing the Dakota Territory into two separate states. In 1889, North and South Dakota were admitted to the Union, and the Madison proposal was quietly shelved.